A Soldier’s Life at the Battles of Saratoga: Inside James Parillo’s Immersive Presentation

On October 25, 2023, museum visitors stepped back into the world of 1777 as Saratoga Springs History Museum Director James Parillo delivered an engaging, deeply detailed presentation on the Battles of Saratoga and the everyday realities of the soldiers who fought, suffered, and persevered during one of the most pivotal moments of the American Revolution.

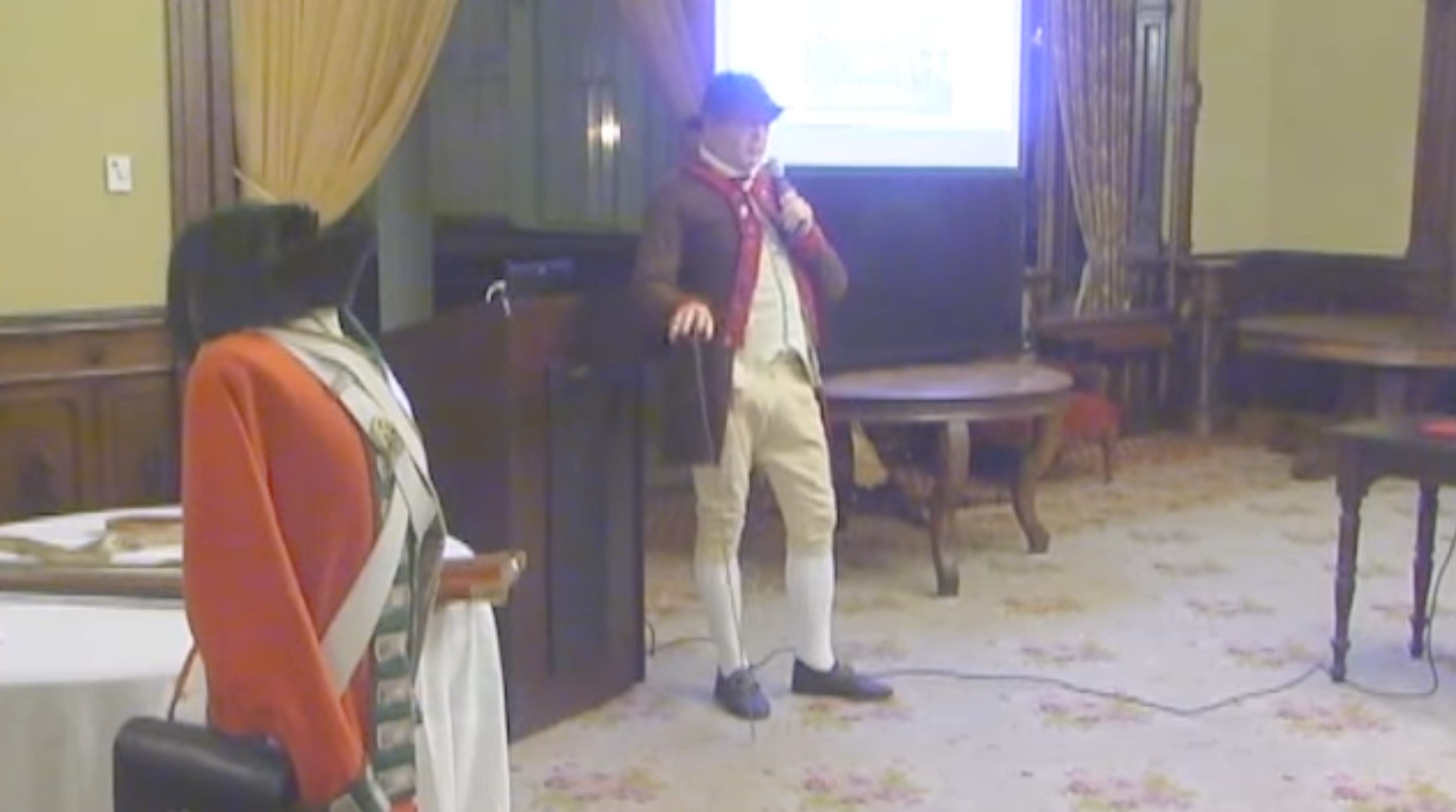

Speaking not just as a historian but as a longtime living-history interpreter, Parillo combined narrative, analysis, and physical demonstration—using his own 18th-century uniform and equipment—to bring the era vividly to life. With artifacts supplied by museum member Charlie Wheeler, including an original musket surrendered at Saratoga, attendees experienced history up close.

Setting the Stage: The Revolutionary War Before Saratoga

Parillo began with a rapid but rich overview of the war as it stood in 1777:

The Revolution had been underway for two years.

The Continental Army struggled with fluctuating enlistments, lack of supplies, and inconsistent leadership.

After devastating losses in New York City and narrow survival after Trenton, the war’s momentum was uncertain.

The Northern Department of the American Army—stationed at Fort Ticonderoga, Fort Edward, and Albany—braced for a major British offensive.

Against this backdrop, British General John Burgoyne launched an ambitious plan to march south from Canada and seize Albany. Parillo introduced the major figures on both sides—Horatio Gates, Benedict Arnold, Daniel Morgan, Baron Riedesel, Simon Fraser, and engineer Tadeusz Kościuszko—creating a clear picture of the personalities who shaped the campaign.

Burgoyne’s Campaign: From Ticonderoga to Disaster

James walked attendees through Burgoyne’s fateful march:

The Fall of Fort Ticonderoga

American forces withdrew after the British famously dragged cannons atop Mount Defiance, making their position indefensible.

Rear-Guard Battles and Delays

Hubbardton (VT) and Fort Anne saw fierce, close-quarters combat.

General Philip Schuyler’s strategic destruction of bridges, roads, and supplies slowed Burgoyne’s advance to a crawl.

The defeat of the British detachment at Bennington cost Burgoyne nearly 700 men—a devastating blow.

With winter approaching, supplies dwindling, and no help arriving from General Howe, Burgoyne pressed on toward Albany, unaware of how decisively the Americans were fortifying the high ground at Bemis Heights.

The First Battle of Saratoga — Freeman’s Farm (September 19, 1777)

Parillo vividly described the battle that unfolded across John Freeman’s farm:

American riflemen under Daniel Morgan ambushed the British advance.

For six hours, the fighting surged back and forth across the fields and woods.

British regiments suffered staggering casualties—some losing over 80% of their men.

Americans withdrew only when German reinforcements threatened their flank.

Though technically a British tactical victory (they held the field), the Americans demonstrated that they could stand toe-to-toe with seasoned European soldiers.

The Second Battle of Saratoga — Bemis Heights (October 7, 1777)

Three weeks later, Burgoyne made a desperate attempt to break through the American lines:

British and German troops pushed into Barber’s Wheat Field.

American forces counterattacked fiercely, driving them back.

Benedict Arnold—already relieved of command—rode into the battle on his own initiative, rallying troops and leading critical assaults.

Arnold was wounded as Americans overran German positions, including the Breymann Redoubt.

British General Simon Fraser was mortally wounded during the action.

By nightfall, Burgoyne’s army was broken and in retreat.

The Siege and Surrender at Saratoga

Surrounded near present-day Schuylerville, cut off from supplies, and outnumbered nearly three to one, Burgoyne surrendered on October 17, 1777.

This “Convention of Saratoga” marked the first major British field army surrender in modern history—a turning point that convinced France to formally ally with the United States and helped change the course of the entire war.

A Soldier’s Experience: Clothing, Gear, and Weaponry

The second half of Parillo’s talk shifted from strategy to daily life.

Dressed in a Continental Army uniform, he demonstrated:

Uniforms

American soldiers wore wool and linen—brown, blue, or whatever colors were available.

British soldiers wore “madder red,” not bright scarlet.

Both armies mixed captured or improvised equipment.

Accoutrements

He displayed original and reproduction gear:

Water flasks

Haversacks

Cartridge boxes

Regimental buckles and insignia

Charlie Wheeler’s artifact table added remarkable authenticity—especially the musket surrendered at Saratoga and later issued to a Massachusetts militiaman.

Weapons

Parillo demonstrated the differences between:

The Musket

Smoothbore, inaccurate beyond 75 yards

Could be loaded in ~20 seconds

Designed for coordinated volleys

Fitted with a terrifying bayonet, the era’s primary shock weapon

The Rifle

Extremely accurate at 100 yards or more

Slow to load

No bayonet

Ideal for sharpshooters like Morgan’s Riflemen

These explanations helped attendees understand why battles unfolded the way they did—and why decisions made in the field often meant the difference between victory and catastrophe.

A Night of Immersive History

From the political missteps of the British high command to the weight of a musket in a soldier’s hands, James Parillo’s presentation offered a powerful, grounded look into the Battles of Saratoga—not as distant textbook events, but as lived human experiences.

Visitors left with a deeper appreciation for:

The chaos and courage of 18th-century warfare

The hardships soldiers endured

The extraordinary significance of Saratoga in securing American independence

And thanks to the generous loan of artifacts from Charlie Wheeler, history felt closer than ever.